Stellar Classifications

Created by Captain Daegan Baas on Tue Dec 10th, 2024 @ 9:50pm

Star Classification

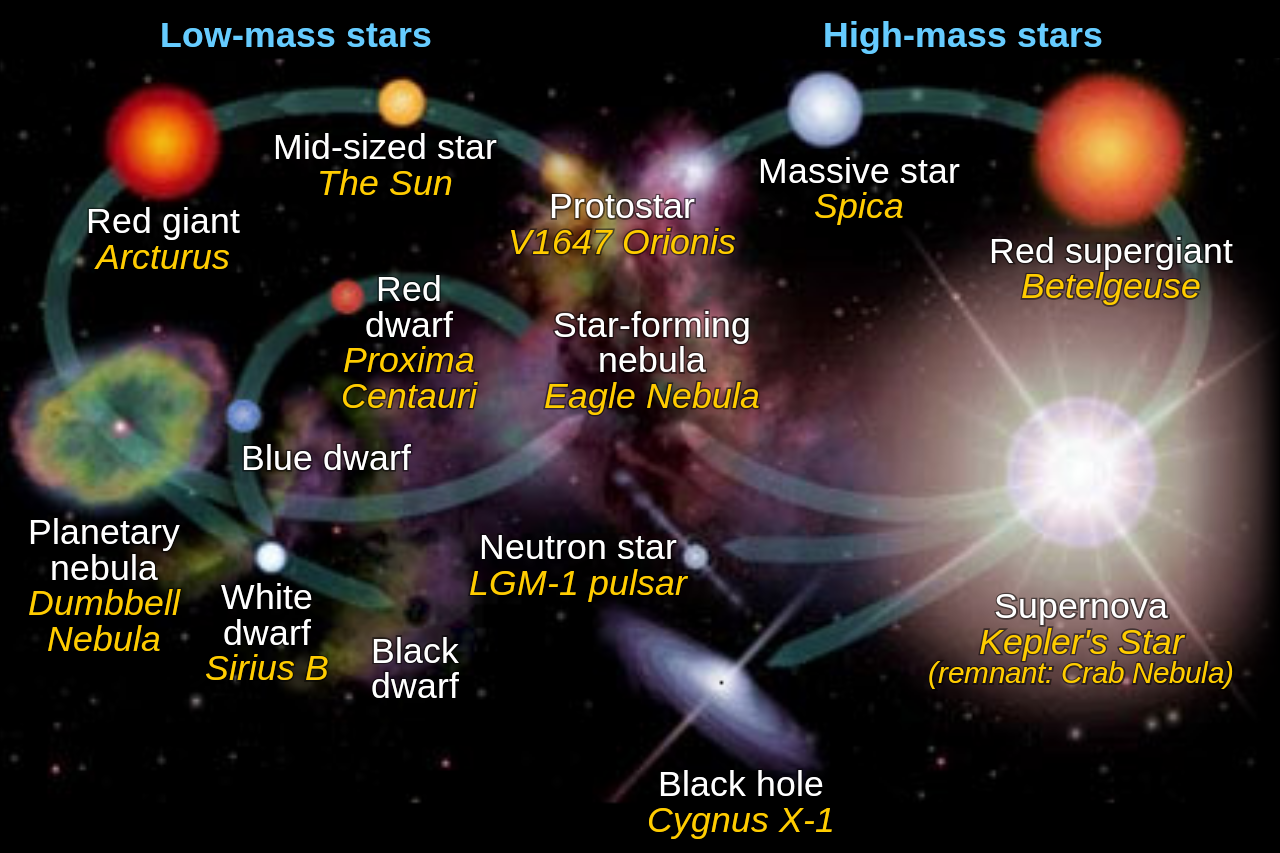

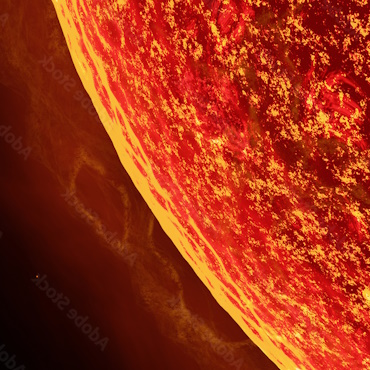

Stars are classified according to a spectral scale which measures the temperature of a star's protosphere. There are four main categories into which they are grouped, including main sequence stars, giant stars, supergiant stars, and dwarfs. Other variations include brown dwarfs and neutron stars. Most stars found in the galaxy are main sequence stars which use a nuclear reaction to fusing hydrogen and converting it into helium to create massive amounts of energy. Most of these stars spend almost their entire lifespan as a main sequence star, but turn into giants when they exhaust their supply of hydrogen and then expand. Low-mass main sequence stars typically turn into giants. After a giant expands to critical mass and sheds its outer layers, forming a Planetary Nebula. Within this nebula, the remaining stellar matter becomes a white dwarf. High-mass main sequence stars turn into supergiants. When a high-mass star expands to form a sugergiant it can explode, in what is called a Supernova, forming a Nebula that may one day form a new solar system. In some cases, a high-mass star will expand, explode, and then collapse to form either a Neutron Star or Black Hole. In some cases the Supergiant will collapse in on itself to create a black hole.

Life cycle of a star

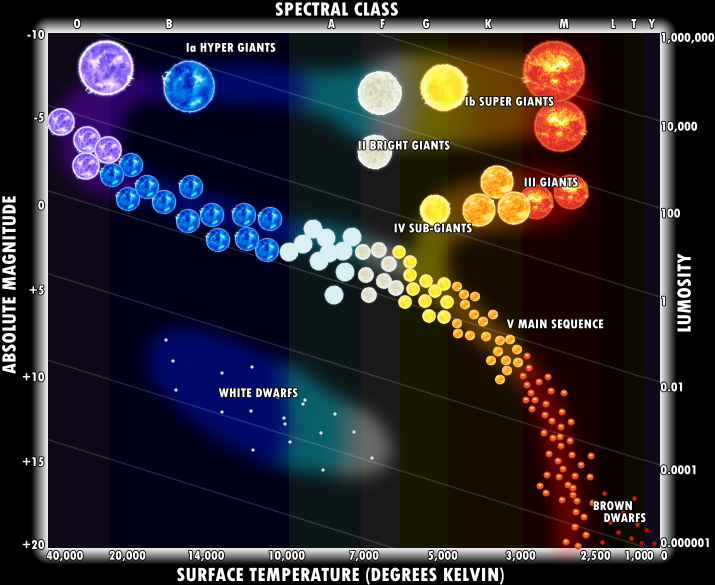

For each spectral class, there are ten subcategories, (0-9) with 0 being the hottest and 9 being the coolest. In order to classify a star, the spectral class must first be identified, followed by an exact assessment of its surface temperature. For example, an A0 is a Spectral Class A star that is burning extremely hot for its class, around 8,500 to 8,700 K. Stars are then sub-categorized by luminosity. Luminosity subclasses include: 1a (luminous supergiants), 1b (less luminous supergiants), II (luminous giants), III (normal giants), IV (subgiants), and V (main sequence and dwarf stars). Using the previous example, an A0V designation now tells us that the star is main sequence Spectral Class A star that is burning extremely hot for its class.

The Hertzsprung-Russell Star Classification Chart

Main Sequence Stars

Main sequence stars are powered by the fusion of hydrogen (H) into helium (He) in their cores, a process that requires temperatures of more than 10 million Kelvin. Around 90 percent of the stars in the Universe are main sequence stars. Main sequence stars typically range from between one tenth to 200 times the mass of Earth's sun or “Sols”.

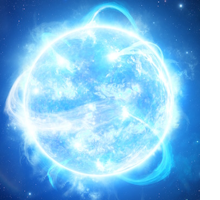

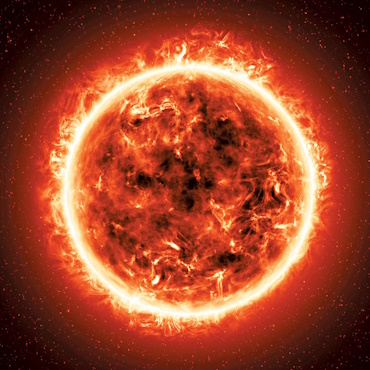

Blue Stars

- Spectral Class: O, B

- Life Cycle: On the main sequence

- Prevalence: ~0.00003% of stars

- Typical temperature: ~30,000K

- Typical luminosity: ~100 to ~1,000,000 sol

- Typical radius: ~2.7 to ~10 sol

- Typical mass: ~2.5 to ~90 sol

- Typical age: < ~40 million years

Examples of blue stars include 10 Lacertae, AE Aurigae, Delta Circini, V560 Carinae, Mu Columbae, Sigma Orionis, Theta1 Orionis C, Zeta Ophiuchi.

Properties

Blue stars are typically hot, O-type stars that are commonly found in active star-forming regions, particularly in the arms of spiral galaxies, where their light illuminates surrounding dust and gas clouds making these areas typically appear blue. Blue stars are also often found in complex multi-star systems, where their evolution is much more difficult to predict due to the phenomenon of mass transfer between stars, as well as the possibility of different stars in the system ending their lives as supernovas at different times.

Blue stars are mainly characterized by the strong Helium-II absorption lines in their spectra, and the hydrogen and neutral helium lines in their spectra that are markedly weaker than in B-type stars. Because blue stars are so hot and massive, they have relatively short lives that end in violent supernova events, ultimately resulting in the creation of either Nebulas, black holes or neutron stars.

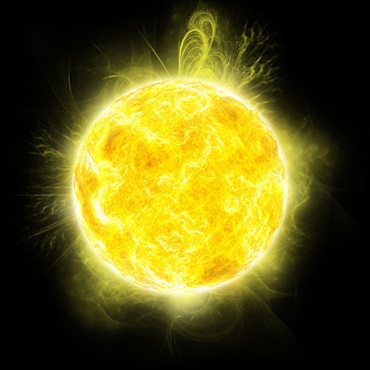

Yellow Dwarfs

- Spectral Type: G

- Life Cycle: On the main sequence

- Prevalence: ~10% of stars

- Typical Temperature: ~5,200K to ~7,500K

- Typical Luminosity: ~0.6 to ~5.0 sol

- Typical Luminosity: ~0.6 to ~5.0 sol

- Typical Mass: ~0.8 to ~1.4 sol

- Typical Age: ~4 to ~17 billion years

Examples of yellow dwarf stars include Alpha Centauri A, Tau Ceti, 51 Pegasi.

Properties

G-type stars are often mistakenly referred to as yellow dwarf stars. Earth's Sun is an example of a G-type star, but it is in fact white, since all the colors it emits are blended together. Nonetheless, even though all the Star’s visible light is blended to produce white, its visible light emission peaks in the green part of the spectrum, but the green component is absorbed and/or scattered by other frequencies both in the star itself, and in Earth’s atmosphere.

Typical G-type stars have between 0.84 and 1.15 solar masses, and temperatures that fall into a narrow range of between 5,300K and 6,000K. Like the Earth's sun, all G-type stars convert hydrogen into helium in their cores, and will evolve into red giants as their supply of hydrogen fuel is depleted.

Orange Dwarfs

- Spectral Type: K

- Life Cycle: On the main sequence

- Prevalence: ~10% of stars

- Typical Temperature: ~3,700K to ~5,200K

- Typical Luminosity: ~0.08 to ~0.6 sol

- Typical Radius: ~0.7 to ~0.96 sol

- Typical Mass: ~0.45 to ~0.8 sol

- Typical Age: ~15 to ~30 billion years

Examples of orange dwarf stars include Alpha Centauri B, Epsilon Indi.

Properties

Orange dwarf stars are K-type stars on the main sequence that in terms of size, fall between red M-type main-sequence stars and yellow G-type main-sequence stars. K-type stars are of particular interest in the search for extraterrestrial life, since they emit markedly less UV radiation (that damages or destroys DNA) than G-type stars on the one hand, and they remain stable on the main sequence for up to about 30 billion years, as compared to about 10 billion years for G-type stars. Moreover, K-type stars are about four times as common as G-type stars, making the search for exoplanets a lot easier.

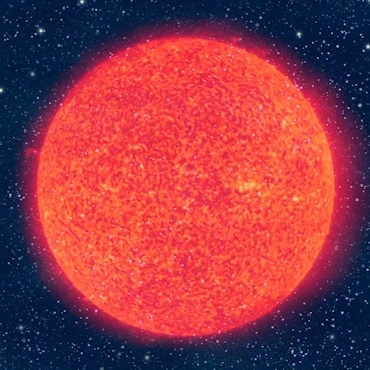

Red Dwarfs

- Spectral Type: K, M

- Life Cycle: Early main sequence

- Prevalence: ~73% of stars

- Typical Temperature: = ~4,000K

- Typical Luminosity: ~0.0001 to ~0.08 sol

- Typical Radius: = ~0.7 sol

- Typical Mass: ~0.08 to ~0.45 sol

- Typical Age: Undetermined, but expected to be several trillion years

Examples of red dwarf stars include Proxima Centauri, TRAPPIST-1.

Properties

Red dwarfs account for the bulk of the Milky Way galaxy's stellar population, but since they are very faint, no red dwarf stars are visible without optical aid. Typically, red dwarf stars that are more massive than 0.35 solar masses are fully convective, which means that the process of converting hydrogen into helium occurs throughout the star, and not only in the core, as is the case with more massive stars.

In this way, the nuclear fusion process is slowed down and at the same time greatly prolonged, which keeps the star at a constant luminosity and temperature for several trillion years. In fact, the process of nuclear synthesis happens so slowly in these that the Universe is not old enough for any known red dwarf star to have aged into an advanced state of evolution.

Giants, Supergiants, and Hypergiants

These massive stars form when a star runs out of hydrogen and begins burning helium. As the star's core collapses and gets even hotter, the resulting heat subsequently causes the star's outer layers to expand outwards. Low and medium-mass stars then evolve into red giants. However, high-mass stars 10+ times bigger than the Sun become super or hypergiant during their helium-burning phase.

These high mass stars fuse helium into heavier and heavier elements until iron is produced. At this point fusion is no longer possible and the star collapses, going supernova.

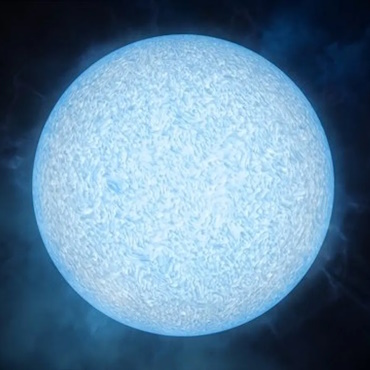

Blue Giants

- Spectral Types: O, B, and occasionally, A-type stars

- Life Cycle: Evolved off the main sequence

- Prevalence: Rare

- Typical temperature: ~10,000K to ~33,000K+

- Typical luminosity: ~10 000 sol

- Typical radius: ~5 to ~10 sol

- Typical mass: ~2 to ~150 sol

- Typical age: ~10 to ~100 million years

Examples of blue giant stars include Iota Orionis, LH54-425, Meissa, Plaskett's star, Xi Persei, Mintaka.

Properties

The term “blue giant star” has no scientific definition, and is commonly applied to a wide variety of stars that have all evolved off the main sequence. However, for practical reasons, stars with luminosity classifications of III and II (bright giant and giant) respectively, are referred to as giant stars purely for convenience, but only when that star is hot enough to be called a blue star, which is usually above around 10,000K. Nonetheless, the term blue giant is often misapplied to some stars simply because they are big and hot.

In practice, however, big stars are referred to as “blue giants” when they inhabit a specific region of the H-R diagram (top of page), rather than because the star meets a specific set of criteria.

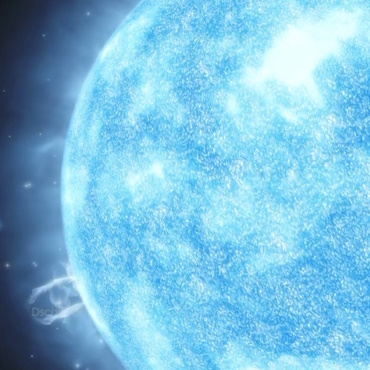

Blue Super & Hypergiants

- Spectral Types: OB

- Life Cycle: Evolved off the main sequence

- Prevalence: Rare to Extremely Rare

- Typical Temperature: ~10,000K to ~50,000K

- Typical Luminosity: ~10,000 to ~1,000,000 sol

- Typical Radius: ~20+ sol

- Typical Mass: ~20 to ~1 000 sol

- Typical Age: = ~10 million years

Examples of Blue Supergiants include UW Canis Majoris (UW CMa) - blue-white (O-type) supergiant; Rigel (ß Orionis) - blue-white (B-type) supergiant; Zeta Puppis (Naos) - blue (O-type) supergiant; 29 Canis Majoris; Alnitak; Alpha Camelopardalis; Cygnus X-1; Tau Canis Majoris; Zeta Puppis.

Exampless of Blue Hypergiants include BP Crucis (Wray 977 or GX 3019-2), Cygnus OB2-12, HT Sagittae, V4030 Sagittarii, Zeta Scorpii

Red Giants

- Life Cycle: Evolved off the main sequence

- Spectral Type: M, K

- Prevalence: ~0.4% of stars

- Typical Temperature: ~3 300 – ~5 300K

- Typical Luminosity: ~100 -~1000 sol

- Typical Radius: ~20 – ~100 sol

- Typical Mass: ~0.3 – ~10 sol

- Typical Age: ~0.1 – ~2 billion years

Examples of red giants include Aldebaran, Arcturus, Gacrux

Properties

Red giant stars are smaller and less massive than red super giants, generally weighing in at between 0.3 to 8 solar masses. In these stars, of which the RBG-branch stars are the most common, hydrogen is still being fused into helium, but in a shell around an inert helium core. Other types of red giant stars include the red-clump stars, in which helium is being fused into carbon, and the asymptotic-giant-branch (AGB) stars, in which helium burning occurs in a shell around a degenerate core of carbon and oxygen, as well as in a shell that surrounds the inner helium-burning shell.

Red Super & Hypergiants

- Life Cycle: Evolved off the main sequence

- Spectral Type: K, M

- Prevalence: ~ 0.0001% of stars

- Typical temperature: ~3,500 to ~4,500K

- Typical luminosity: ~1,000 to ~800,000 sol

- Typical radius: ~100 to ~1650 sol

- Typical mass: ~10 to ~40 sol

- Typical age: ~3 million to ~100 million years

Examples of Red Supergiants include Alpha Herculis (Rasalgethi), Psi1 Aurigae, 119 Tauri, Antares, Betelgeuse.

Examples of Red Hypergiants include Mu Cephei, NML Cygni, VV Cephei A, VY Canis Majoris

Properties

Red supergiant stars are stars that have exhausted their supply of hydrogen at their cores, and as a result, their outer layers expand hugely as they evolve off the main sequence. Stars of this type are among the biggest stars known in terms of sheer bulk, although they are generally not among the most massive or luminous. In rare cases, red super & hypergiant stars can be massive enough to fuse very heavy elements (including iron) that are arranged around the core in a way that somewhat resembles the layers of an onion, only without sharp divisions. Red supergiants that create heavy elements eventually explode as type-II supernovas.

Dead Stars

The following are dead stars, which no longer have fusion processes taking place in their cores:

White Dwarfs

- Life Cycle: No longer producing energy

- Spectral Type: D (Degenerate)

- Prevalence: ~4% of stars

- Typical temperature: ~8,000K to 40,000K

- Typical luminosity: ~0.0001 to ~100 sol

- Typical radius: ~0.008 to ~0.2 sol

- Typical mass: ~0.1 to ~1.4 sol

- Typical Age: Largely undetermined, but estimated to be between ~100,000 years to ~10 billion years

Examples of white stars include Sirius B, Procyon B, Van Maanen 2, 40 Eridani B, Stein 2051 B.

Properties

White dwarf stars are the cores of low and intermediate mass (typically lower than 3 solar masses) stars that have blown off their outer layers late in their lives. These stellar remnants no longer produce energy to counteract their mass, and are supported against gravitational collapse by a process called electron degeneracy pressure. While the theoretical maximum mass of a white dwarf star cannot exceed 1.4 solar masses (Chandrasekhar limit), this value does not include the effects of rotation. In practice, this means that rapidly spinning white dwarf stars can exceed the maximum mass limit by a significant margin.

Some types of white dwarfs, most notably carbon-oxygen stars, can also survive several nuclear explosions on their surfaces when the mass of accreted material pulled from normal companion stars exceed a critical level.

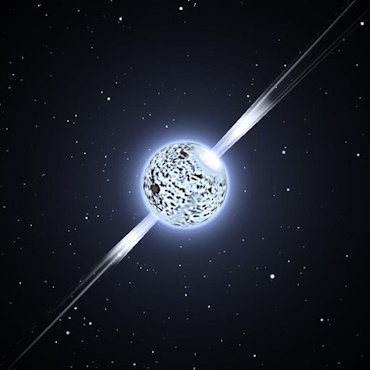

Neutron Stars

- Life Cycle: No longer producing energy

- Spectral Type: D

- Prevalence: ~0.7% of stars

- Typical temperature: ~ 600,000K

- Typical luminosity: Typically very low due to their small size

- Typical radius: ~5 to ~15 km

- Typical mass: ~1.4 to ~3.2 sol

- Typical Age: Largely undetermined, but estimated to be between ~100,000 years to ~10 billion years

Examples of neutron stars include PSR J0108-1431; LGM-1 (first recognized radio-pulsar); PSR B1257+12 (first neutron star discovered with planets); SWIFT J1756.9-2508 (a millisecond pulsar with a stellar-type companion with planetary range mass); PSR B1509-58 (source of the “Hand of God” photograph taken by the Chandra X-ray Observatory); PSR J0348+0432 (most massive neutron star with a well-constrained mass of 2.01 ± 0.04 solar masses).

Properties

Neutron stars are the collapsed cores of massive stars (between 10 and 29 solar masses) that were compressed past the white dwarf stage during a supernova event. In this state, the entire mass of the stellar remnant consists of neutrons, particles that are marginally more massive than protons, but carry no electrical charge. Neutron stars are supported against their own mass by a process called “neutron degeneracy pressure”, but the process of gravitational collapse into a black hole may continue if the remnant has more than 3 solar masses. However, neutron stars with very high spin rates may be able to resist collapsing into black holes even if they have substantially more than 3 solar masses.

Note that while Pulsars are often referred to as a class of star, pulsars are merely energetic neutron stars that emit huge quantities of radiation in various frequencies.

Black Dwarfs

Black dwarfs are hypothetical stars that are theorized to be white dwarfs that have radiated away all their leftover heat and light. However, white dwarfs live for an extremely long period of time, with many of the ones detected so far being in excess of 10 billion years, meaning that no black dwarfs have had enough time to form in the Universe’s 13.8 billion-year history.

Black Holes

While smaller stars may become a neutron star or a white dwarf after their fuel begins to run out, larger stars with masses more than three times that of our sun may end their lives in a supernova explosion. The dead remnant left behind with no outward pressure to oppose the force of gravity will then continue to collapse into a gravitational singularity and eventually become a black hole, with the gravity of such an object so strong that not even light can escape from it.

However, there are a variety of different black holes. For instance, ‘stellar-mass’ black holes are the result of a star around 10 times heavier than the Sun ending its life in a supernova explosion, while ‘supermassive’ black holes found at the center of galaxies may be millions or even billions of times more massive than a typical stellar-mass black hole. Well-known examples of black holes include Cygnus X-1, and Sagittarius A.

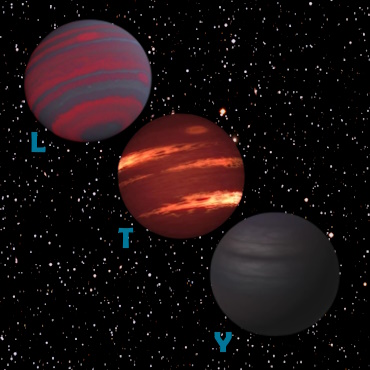

Failed Stars

Failed stars, typically referred to as Brown dwarfs, are sub-stellar objects that fill the gap between the most massive gas planets, and the least massive true stars. These objects, while not big enough to sustain nuclear fusion of ordinary hydrogen into helium in their cores, but are massive enough to emit some light and heat from the fusion of deuterium. The most massive ones (> 65 MJ) can fuse lithium.

Brown Dwarfs

- Spectral Type: L, T, Y

- Life Cycle: Non-main sequence

- Prevalence: ~1% to ~10% of stars

- Typical temperature: ~300K to ~2,800K

- Typical luminosity: ~0.00001 sol

- Typical radius: ~0.06 to ~0.12 sol

- Typical mass: ~0.01 to ~0.08 sol

- Typical age: Undetermined, but suspected to be several trillion years

Examples of brown dwarfs include Gliese 229 B, 54 Piscium, Luhman 16.

Note that while brown dwarf stars exist in large numbers, Luhman 16 is the closest known example, being only 6.5 light years away from Earth.

Properties

Brown dwarf stars fall into the mass range of 13 to 80 Jupiter-masses, with sub-brown dwarf stars falling below this range, and the least massive red dwarf stars falling above it. Note though that brown dwarf stars mostly do not emit visible light, but where they do, they can occur in a wide range of colors. Human vision would likely perceive most stars of this type as deep red or dark magenta.

Categories: Stellar Cartography